Stories of book challenges and bans in schools have dominated the educational news circuit in recent months, and for good reason. The rate of book challenges has been on the rise over the last three years, with the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom tracking the highest number of challenges they’ve ever recorded—1,269, in fact—in 2022.

This issue affects not only students but also teachers, especially those in English language arts. For more insight, we surveyed our ELA educator subscribers and asked them to share their thoughts on book challenges taking place in many schools across the country. When we constructed this survey, we predicted the results would be clearly skewed in one direction, considering our audience. But as you will see, there is more nuance to the responses than anticipated. We’ll go over the survey results in this post.

The final question of the survey gave respondents the option to share any thoughts they have about book challenges under the condition of anonymity. Many answers corresponded with topics covered by other questions in the survey. We’ll share some of these responses throughout this post. Some statements have been edited for length or to maintain anonymity.

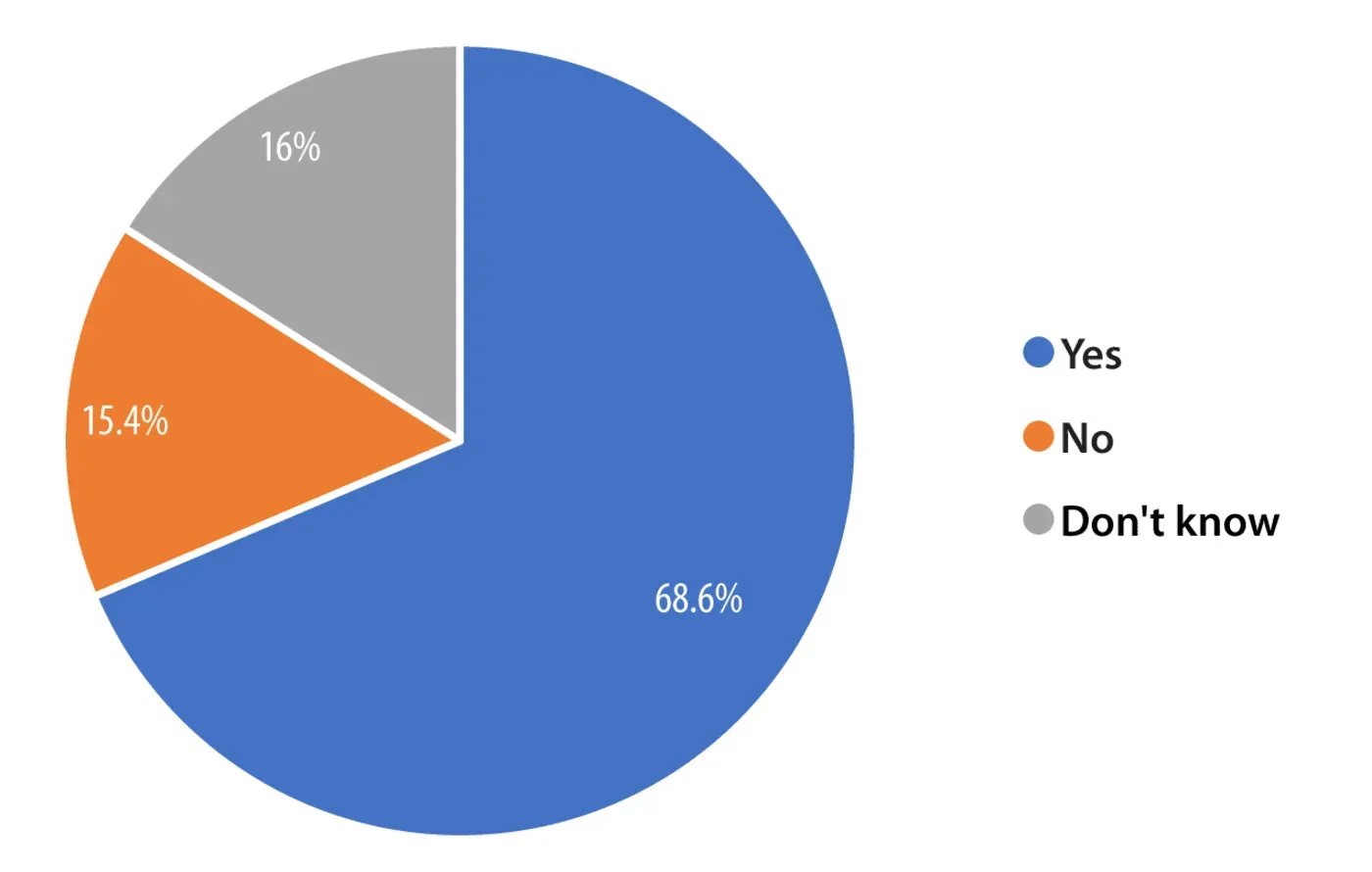

In your school or district, are parents/guardians allowed to opt their child out of literature units for any reason?

Allowing parents and/or guardians to make choices about their child's education respects their right to raise their child according to their own convictions. Some parents may find that the materials in certain literature units conflict with their values or beliefs. In response, schools across the country sometimes allow parents to opt their child out of units as they see fit. 68.6% of survey respondents said their school or district lets parents do this, while 15.4% said they do not. 16% didn’t know if their school or district offers this policy.

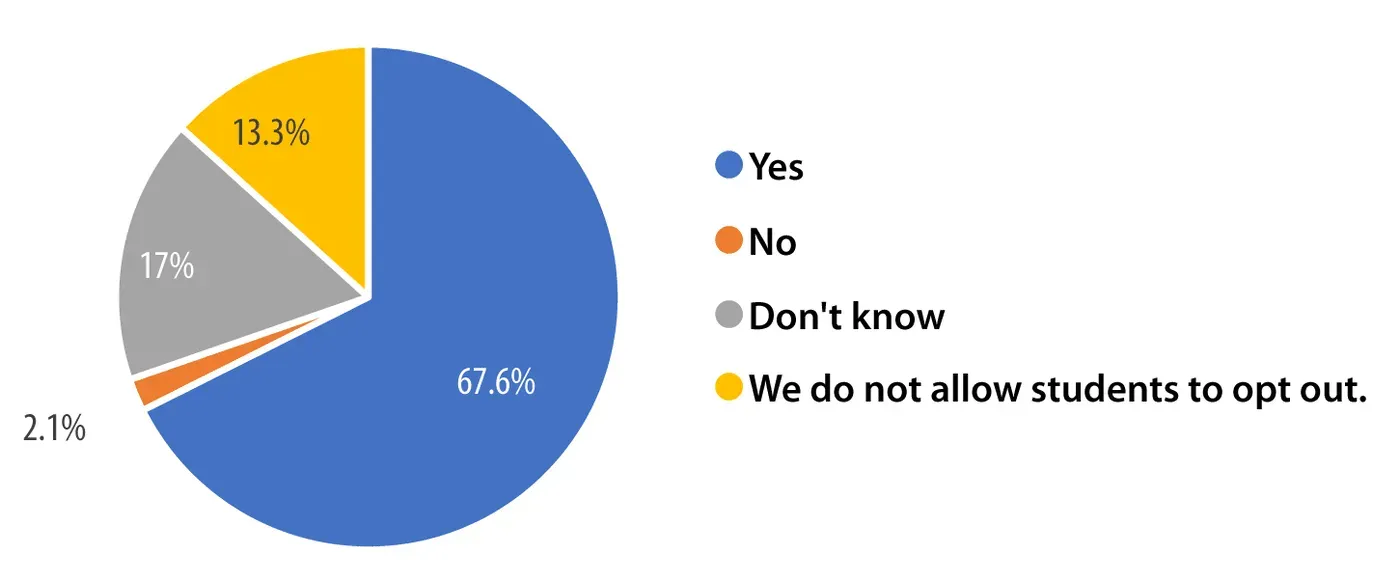

If students are allowed to opt out of literature units, are you required to provide alternative books and/or lessons?

In the event that a parent decides to opt their child out of a literature unit, some schools require that the teacher provide the student with an alternative unit. These lessons are meant to cover the same concepts or themes and should be as academically rigorous as the original unit. 67.6% of survey respondents said they’re required to provide alternative lessons. Comparatively, just 2.1% said no. The remaining respondents either didn’t know if they were required (17%) or stated that their school or district does not allow students to opt out (13.3%).

For some teachers, the problem is not the request for an alternative unit itself, but the amount of requests taking place. As one respondent stated:

“We have spent years creating and refining our curriculum which has been posted for public comment and was passed. Now we have parents randomly coming in to state they ‘don't want [their] child reading that book.’ Not only do I have to teach the other children, but now I have to come up with a completely different [unit] to meet the same standards and is similar in theme for the written part of the assignment. If parents are permitted to do this for every selection in the curriculum, then it is a huge drain on teacher time which could be better invested in the students.”

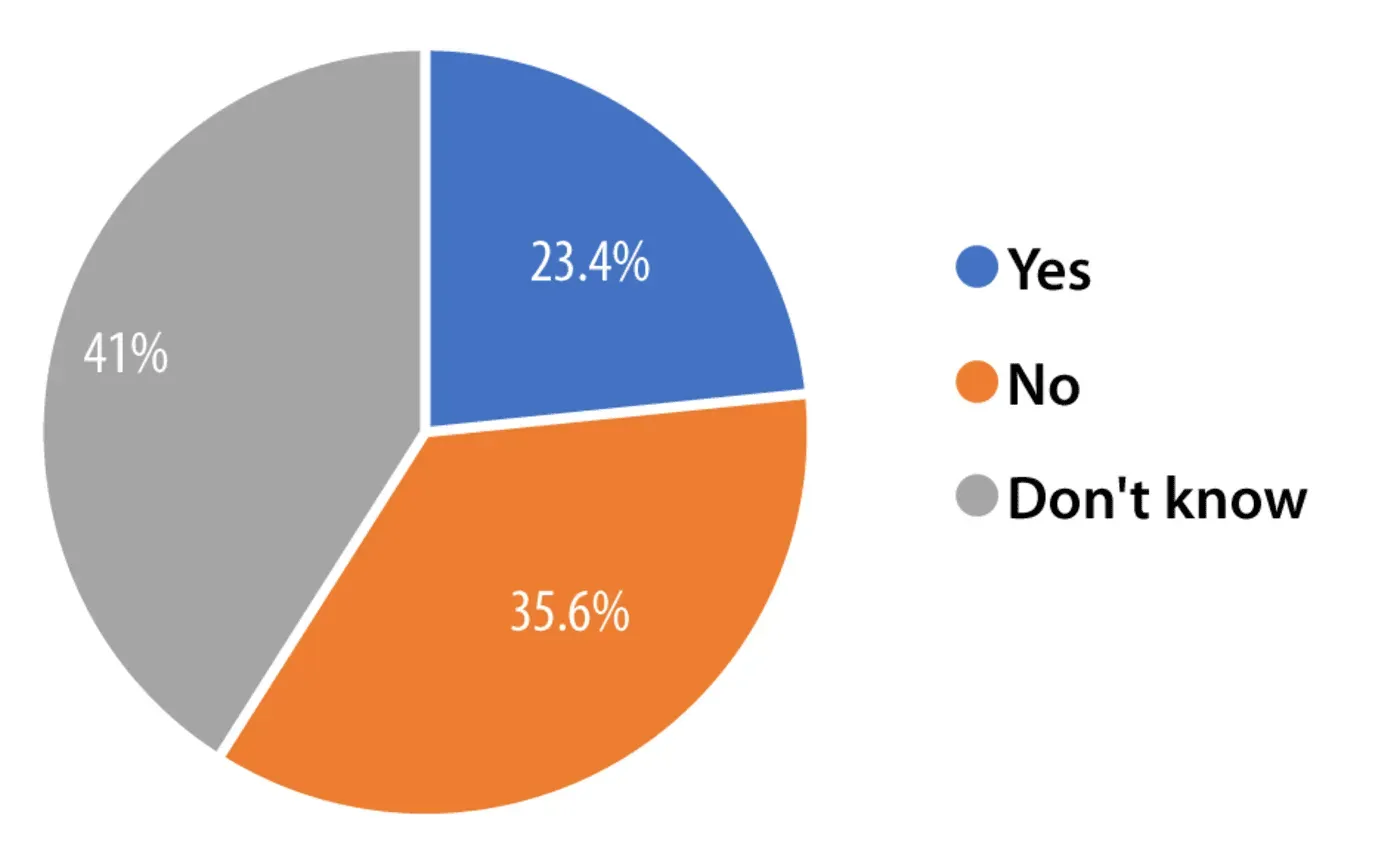

Does your school or district have a formal reconsideration policy for educational resources and/or library materials?

Schools or districts sometimes require that potentially objectionable materials undergo a formal reconsideration process before they’re removed from the curriculum or library shelves. These policies are designed to provide a fair and systematic way of addressing the concerns of parents or community members while preserving the right to freedom of inquiry for students.

Just 23.4% of those surveyed said their school or district has a formal reconsideration policy in place. 41% stated they don’t know if such a policy exists.

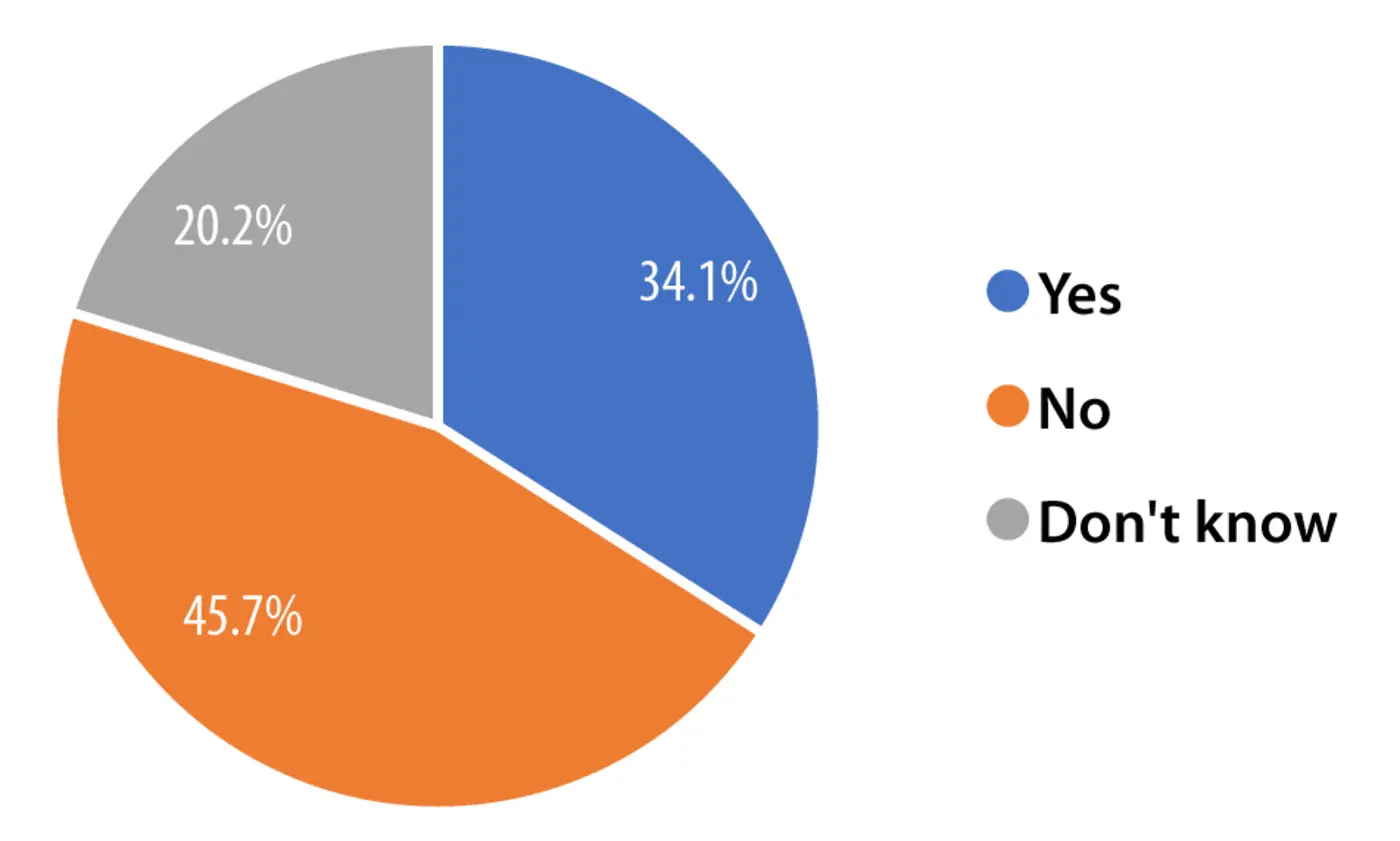

To your knowledge, have parents or community members attempted to ban certain books in your school or district within the past year?

According to data provided by the American Library Association, in 2022, 30% of book challenges in public libraries and schools were initiated by parents. In our survey, 34.1% of respondents said parents or community members have attempted to ban books in their school or district within the past year. The majority (45.7%) said no. 20.2% were unsure.

Several survey respondents made it clear they advocate for parent choice. However, some believe one parent’s decision for their child should not affect what other parents’ children are able to read:

“It's the parents' choice as to what content they want their child to be exposed to and whether it is appropriate. Parents have a right to know what their child is reading and have a say in whether it is appropriate or not.”

“I believe that children and their parents should only decide books for their own family, not all others.”

“Parents should have the ability to say that they're not comfortable with their child reading something, BUT they should have no say in what other people's children are allowed to read. Just because a book makes you or your child uncomfortable, doesn't mean that it needs to be banned.”

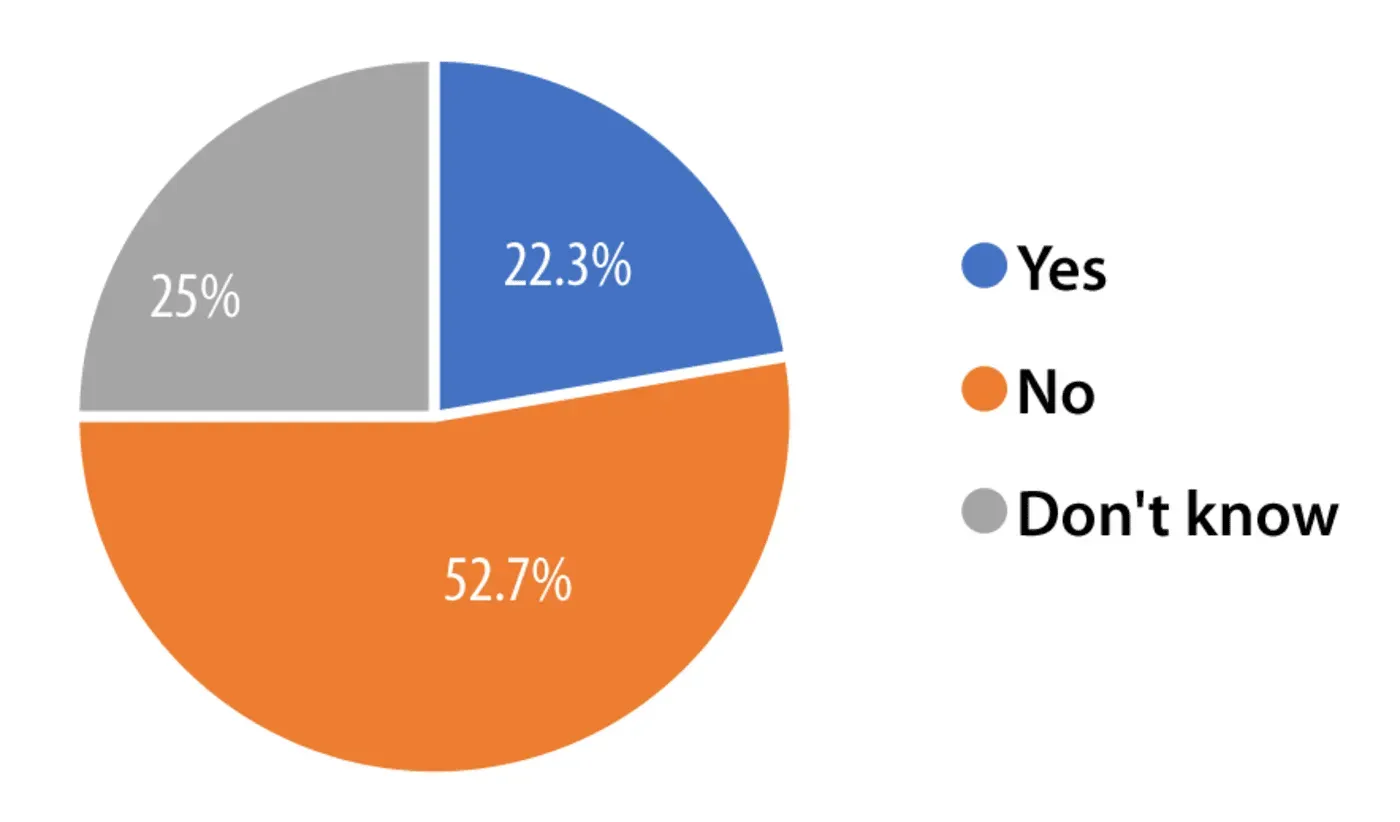

To your knowledge, have politicians, elected officials, or affiliated groups (of any party) attempted to ban certain books in your school or district within the past year?

As we’ve seen in recent news, politics sometimes plays a role in book challenges, with affiliated groups, aspiring politicians, and elected officials advocating for the removal or replacement of some books. When it comes to their own school or district, 52.7% of survey respondents said there hasn’t been a challenge by politicians or groups within the last year, while 22.3% have seen attempts made. A quarter of respondents didn’t know if these types of challenges took place.

“Some [of] our challenged books are purely based on political affiliation and trying to be elected into a local government office. Only a few, very small number of parents want modern young adult books banned. These are often written by diverse authors and about minorities. These parents opt for classical novels.”

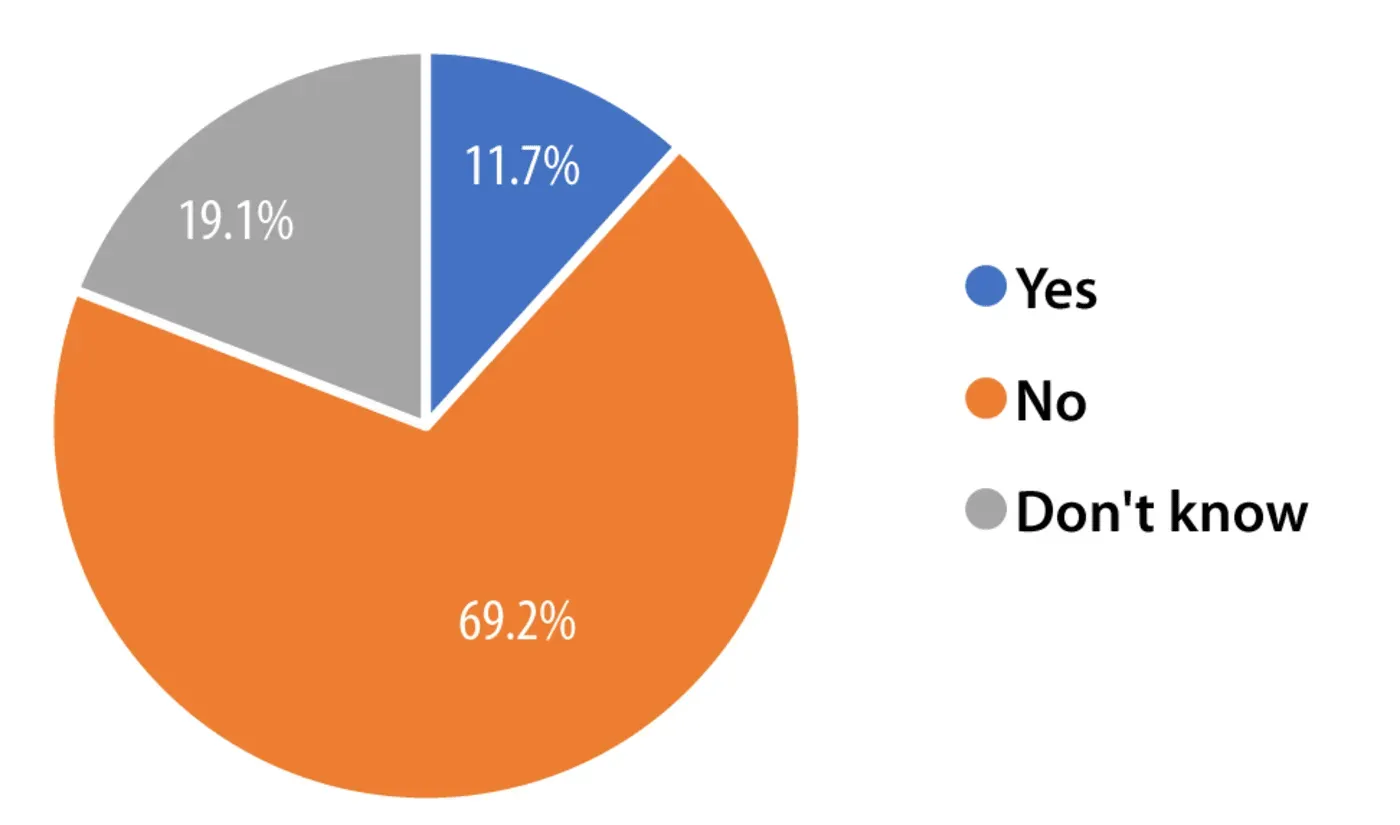

To your knowledge, has there been a successful book ban in your school or district within the past year?

Book challenges may take place, but that doesn’t always mean they achieve their goals. While 11.7% of survey respondents said there was a successful book ban in their school or district within the last year, the majority of survey respondents (69.2%) said there was not. 19.1% were unsure if one occurred.

Those surveyed who answered “Yes” were asked to share which books were removed. Here are the most common responses:

The Bluest Eye |

One Hundred Years of Solitude |

The Perks of Being a Wallflower |

The Handmaid's Tale |

To Kill a Mockingbird |

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl |

Out of Darkness |

Looking for Alaska |

Gender Queer |

Monster |

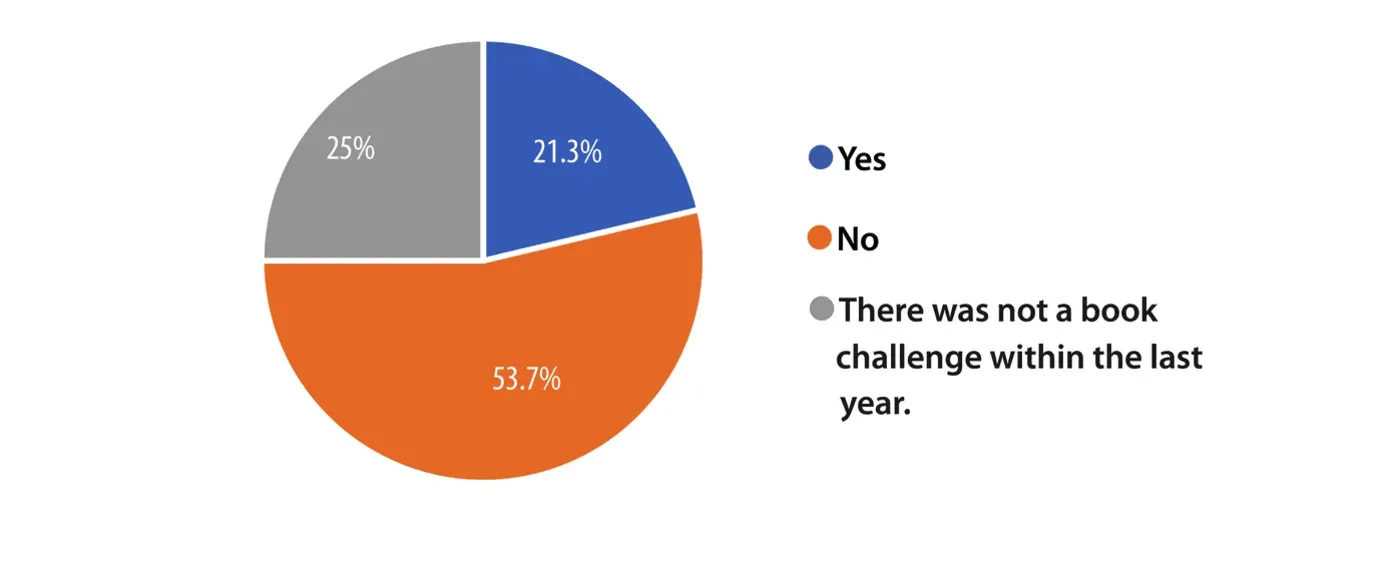

Has a book challenge in your school or district, successful or not, personally affected you within the past year?

Of the 75% of survey respondents whose school or district experienced a book challenge, over half (53.7%) were not personally affected compared to 21.3% who were. The remaining 25% of survey respondents indicated there was not a book challenge at their school or district within the last year.

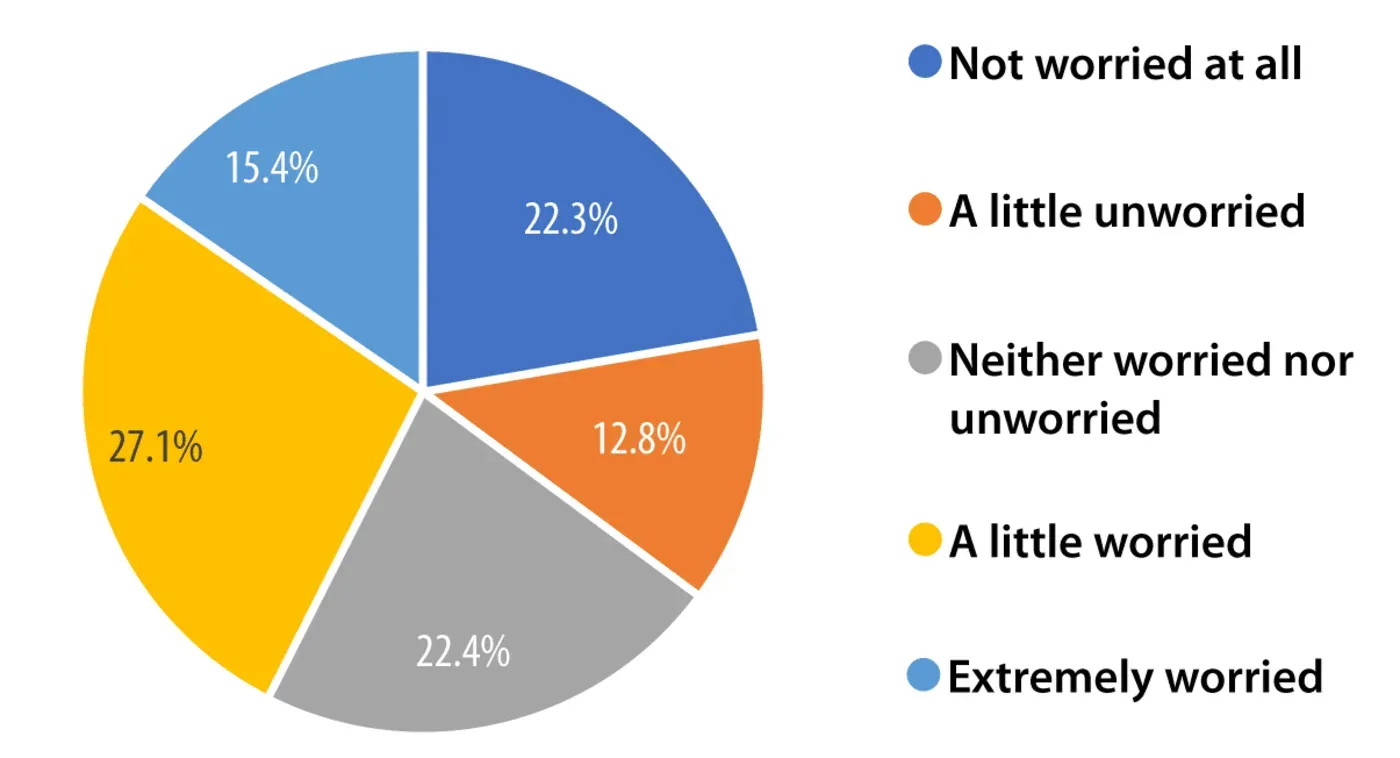

How worried are you about the books in your classroom being challenged?

When asked if they were concerned about challenges against books in their classroom specifically, 22.3% of respondents were not worried at all; 12.8% were not very worried; 27.1% were a little worried; and 15.4% were extremely worried. 22.4% were neither worried or unworried

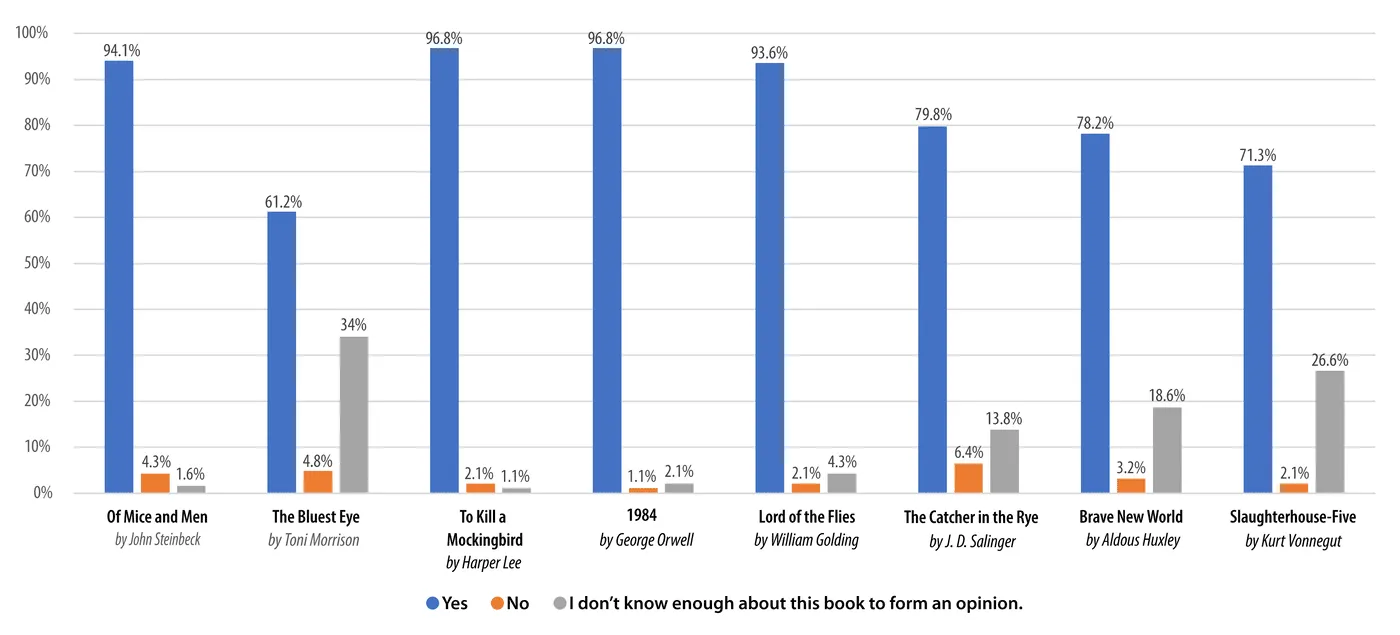

Here is a list of classic books that have historically been the target of book challenges. Many of the complaints focused on the books’ violent, racist, and/or sexual themes, among other aspects. Do you believe the literary value of each book outweighs its potentially questionable content?

Here, we presented eight classic books that are commonly challenged in schools because of objectionable content. We wanted to know if the ELA educators taking our survey believe that these books still offer literary merit that outweighs their controversial content.

Of Mice and Men, Lord of the Flies, To Kill a Mockingbird, and 1984 all received a resounding “yes,” with 1984 and To Kill a Mockingbird both scoring the highest votes at 96.8% each. The Catcher in the Rye, Brave New World, and Slaughterhouse-Five trailed behind at 79.8%, 78.2%, and 71.3% respectively. The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison was last at 61.2%, as 34% of respondents didn’t know enough about the book to form an opinion.

Some of the written responses offered insight on the challenges of teaching the classics to today’s students:

“I believe that oftentimes books are challenged because they are introduced at too early an age [to] even understand the content they are reading. For example, even though Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird is a young girl, it does not mean that a girl that age could read the book and understand the context of what is being read. Lord of the Flies is a wonderful text, but we save it for our seniors because it takes maturity to read it … I worry some teachers do not think about that when assigning texts. Thus, they invite challenges.”

“While parent/political/community attempts to ban books is important, I think it’s equally important that we, as educators, consider what books are still appropriate for students in 2023. Many students from marginalized groups are stuck in classes reading books with racist language (and likely taught by white teachers). There’s a nuanced difference, I think, between parents/groups trying to ban any book that even hints at LGBTQ+ issues and teachers collectively deciding that Steinbeck’s rampant use of the n-word does more curricular harm than good.”

“The majority of literature that is banned for sensitive material actually teaches why it is inappropriate. For example, Harper Lee’s classic is challenged for racism and use of ‘that word,’ but the book is a scathing attack on bigotry of all kinds.”

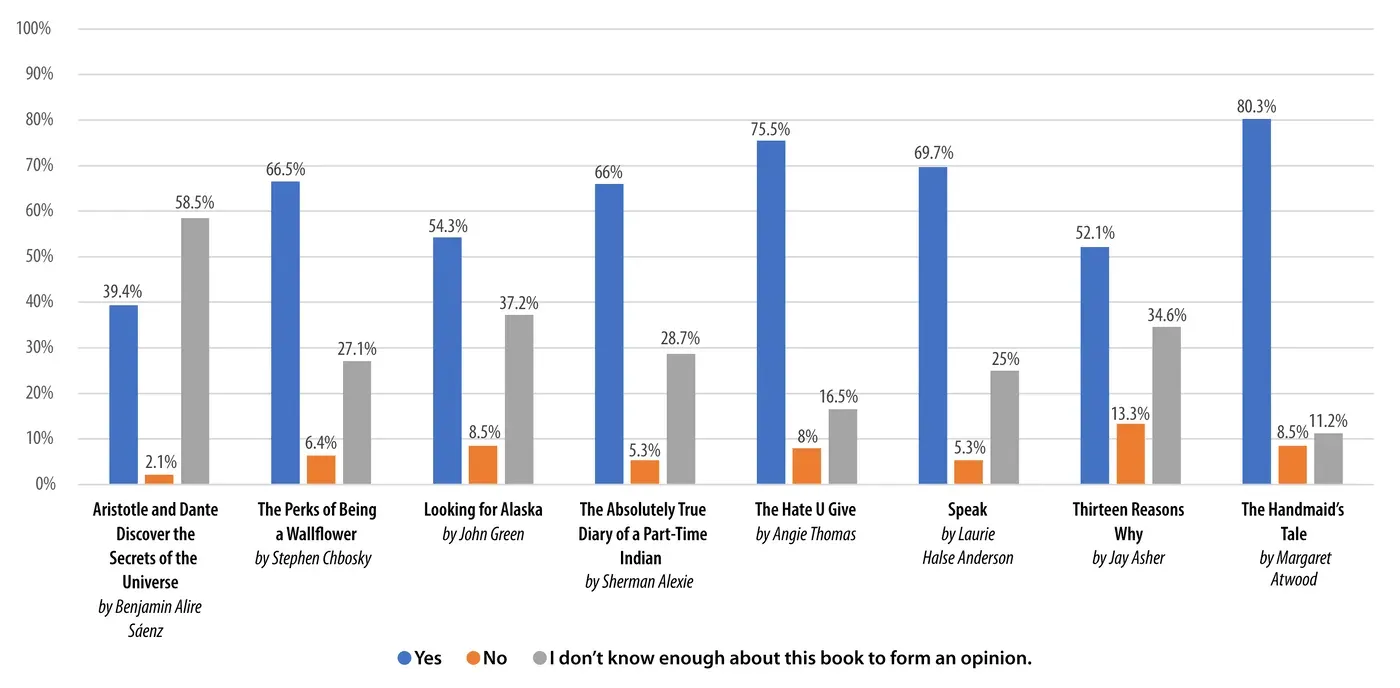

The following are several contemporary books that have been subject to challenges in 2022 and 2023. Many of the complaints focused on profanity, sexual references, violence, and racial content. Do you believe the literary value of each book outweighs its potentially questionable content?

Next, we looked at eight books published in the last few decades that have frequently appeared in banned books lists and news articles. We asked the same question as we did for the classics: Does the literary merit of each title outweigh its objectionable content? Answers here weren’t as definitive as the previous section because a fair amount of respondents didn’t know enough about the books to decide one way or the other.

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale received the most “yes” votes at 80.3%, followed by Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give (75.5%), Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak (69.7%), Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower (66.5%), Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (66%), John Green’s Looking for Alaska (54.3%), Jay Asher’s Thirteen Reasons Why (52.1%), and Benjamin Alire Sáenz’s Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe (39.4%).

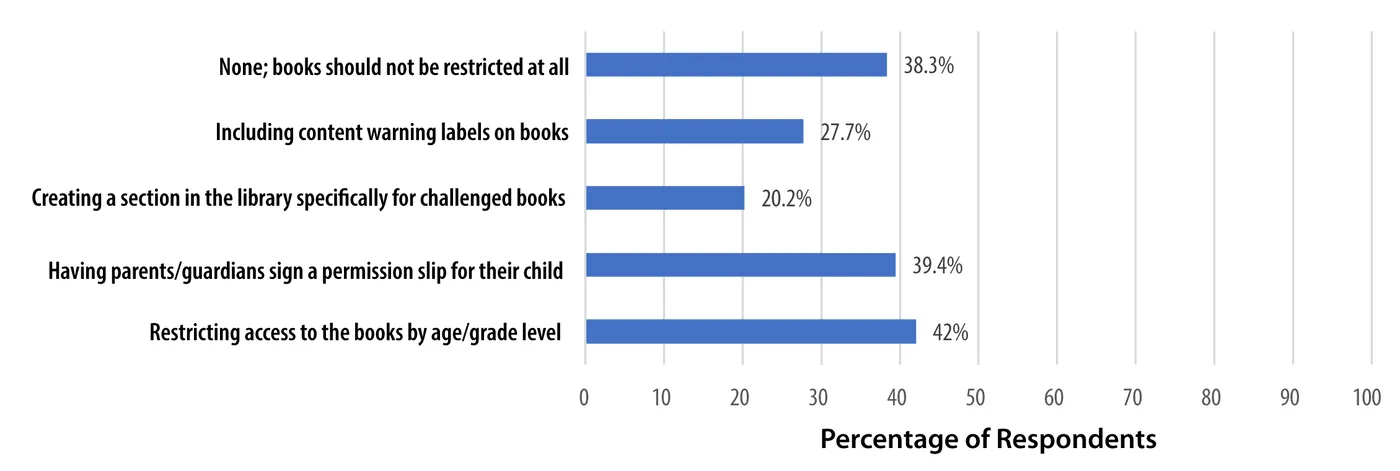

Instead of completely removing certain books from a school or library, in your opinion, what would be a reasonable compromise?

So, there’s a book challenge at a school or library. What else can be done besides outright removing the book from the building? We offered our survey respondents some options.

The permission slip is already a common practice in many schools. Parents or guardians must grant their child access to materials in writing. 39.4% of respondents thought this was a reasonable compromise.

42% of respondents agreed with restricting access to the books by age or grade level, while 20.2% supported creating a section in the library exclusively for challenged books.

“There should be some restrictions on content at the elementary level since students are usually required to read, but at the high school level, the students are mature enough to know if they start reading a book that contains themes that they or their families wouldn’t approve of, they can simply return the book and choose another.”

The “museum” analogy in this response offers a novel way of looking at the issue:

“What most people want is curation, or the creation of a collection that is fitting for a particular audience. Museums are the ultimate place of curation, as they have different exhibits featuring different styles while ensuring everything in the exhibit is of high quality. At the level of an elementary school, the library would be curating its collection to suit its students if it did not include graphic content better suited for older students … The more-mature content is not what that ‘museum’ is about. Certainly, there are topics that require delicacy which caregivers should be a part of, and there should be age-appropriate books accessible to the parents as a resource. This is where dedicated sections of books with challenging materials might be beneficial for calming the anxieties that exist.”

Another common suggestion is including content warning labels on books, a measure supported by 27.7% of survey respondents. These content advisories could act similarly to the rating systems for other media, like film, TV, video games, and music.

“Parents do have a right to know what content their child is consuming … A kid should be allowed to know if a book has anything like graphic violence or even the death of a pet so they, too, can be in control of what they’re consuming. A content advisory system, such as what exists for other forms of media, would serve both students and parents.”

“While some books do have material that is neither age nor school appropriate, some people have gone overboard in choosing books that they deem meritless. The simplest way to fight this is to rate books the same way we rate movies, television, and music.”

Finally, 38.3% of respondents said there should be no restrictions on books at all.

The following questions asked respondents to share whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements. These are messages commonly conveyed by different sides of the book challenge debate.

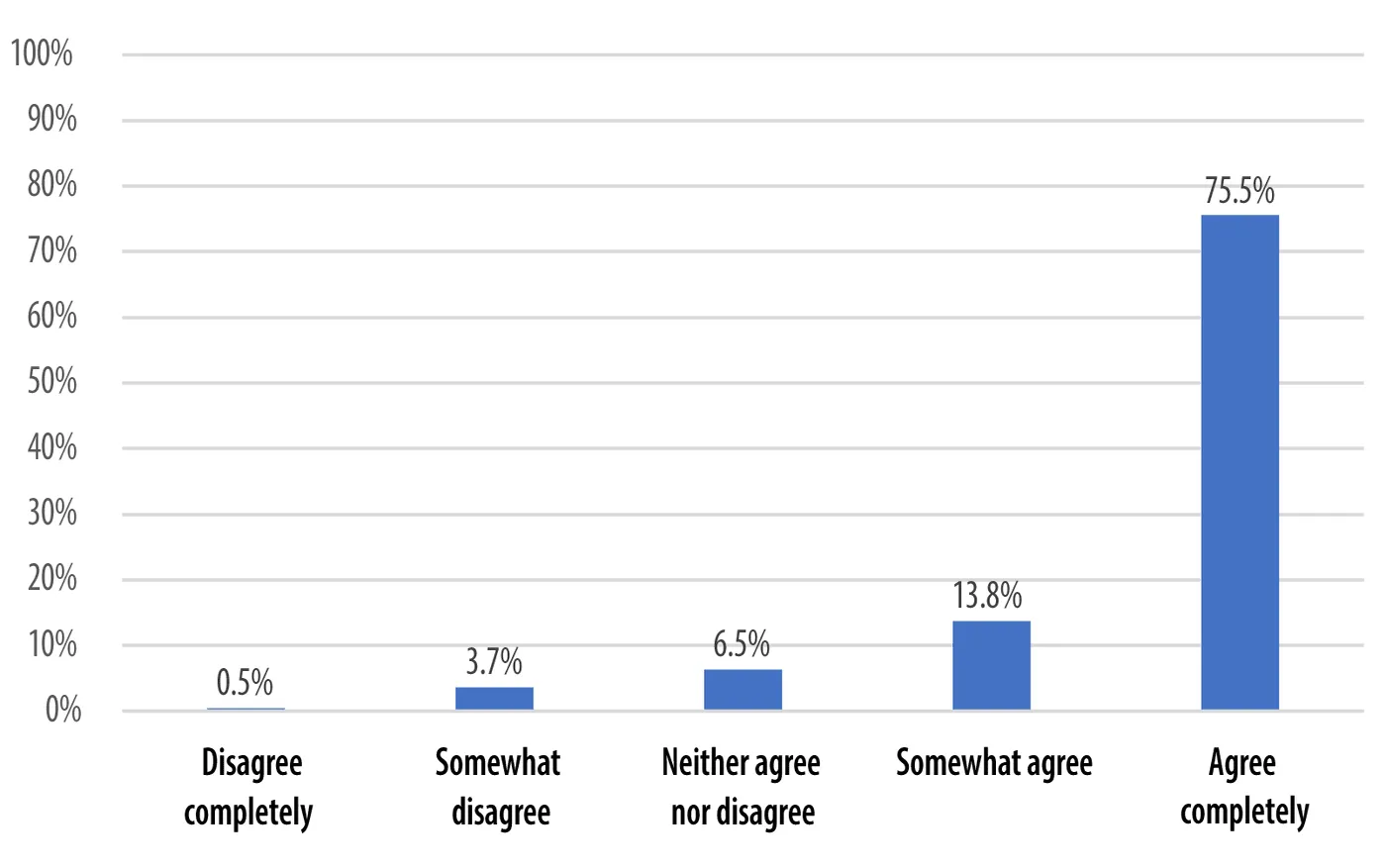

Banning books is a violation of free speech.

Opponents of book challenges often bring up the “free speech” argument; that is, banning books hinders free expression, a right protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution. Attempts to censor or challenge books may be infringing on that right, especially if they’re occurring in publicly funded places like schools or libraries.

When asked if they think banning books is a violation of free speech, the majority of respondents agreed completely (75.5%), compared to just 0.5% who thought the opposite.

“It becomes very challenging to find pieces that students connect with if the government dictates what types of books are allowed to be in our libraries or classrooms.”

Some hypothesize that the threat of a book challenge alone can create a “chilling effect,” in which individuals and authors may self-censor out of fear that their expressions may be banned or censored, undermining free speech and the open exchange of ideas. This response from one educator describes this phenomenon:

“The fear mongering on both sides have gone too far. I teach in [state name redacted] and so far we have been more affected by the fear of books being challenged or banned than actual challenges or bans. However, even though actual bans are few and far between, just the fear alone leads to a self-censoring that to me is actually a serious threat to free speech.”

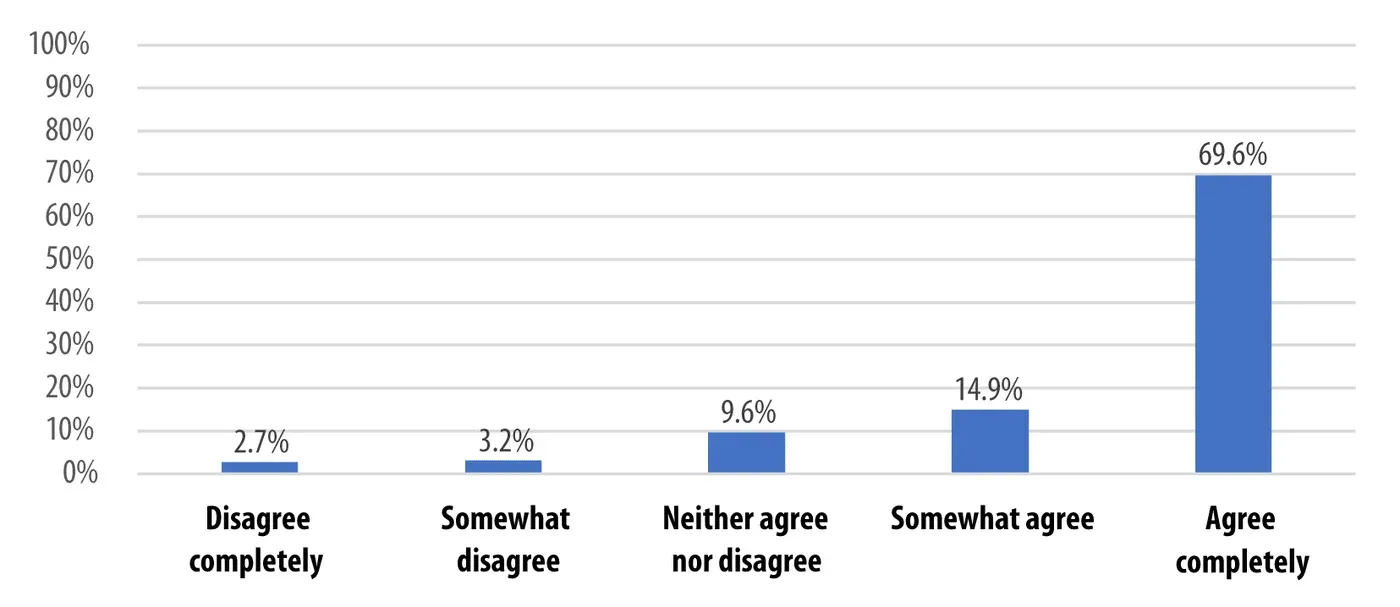

School librarians are qualified to select books that are appropriate for their school’s demographic.

A recurring topic in discussions about book challenges revolves around the question of responsibility: Who should be held accountable for introducing books containing potentially objectionable content into schools? For some, the answer would be the librarian.

When asked if they think school librarians are qualified to select books that are appropriate for their school’s demographic, 69.6% of respondents agreed completely, and the numbers dropped from there: somewhat agree (14.9%), neither agree nor disagree (9.6%), somewhat disagree (3.2%), and disagree completely (2.7%).

Some respondents noted that teachers also play a large role in book selection and should be part of the conversation:

“In reference to your question regarding school librarians’ qualifications for selecting books, I would add that teachers are also qualified to select books.”

“I feel as an English educator, school districts should leave it up to teachers and librarians to decide what is appropriate material to be taught to students. It should be solely based on the maturity level of students in the schools.”

“Librarians are professionals and are qualified to select reading materials for their patrons. I’m still very puzzled by individuals and groups that feel as if they have [the] right to manage another parent’s agency to choose reading material for their own children. If only a tenth of this energy spent on banning books was spent monitoring what minors are able to access online, then that would be energy well spent.”

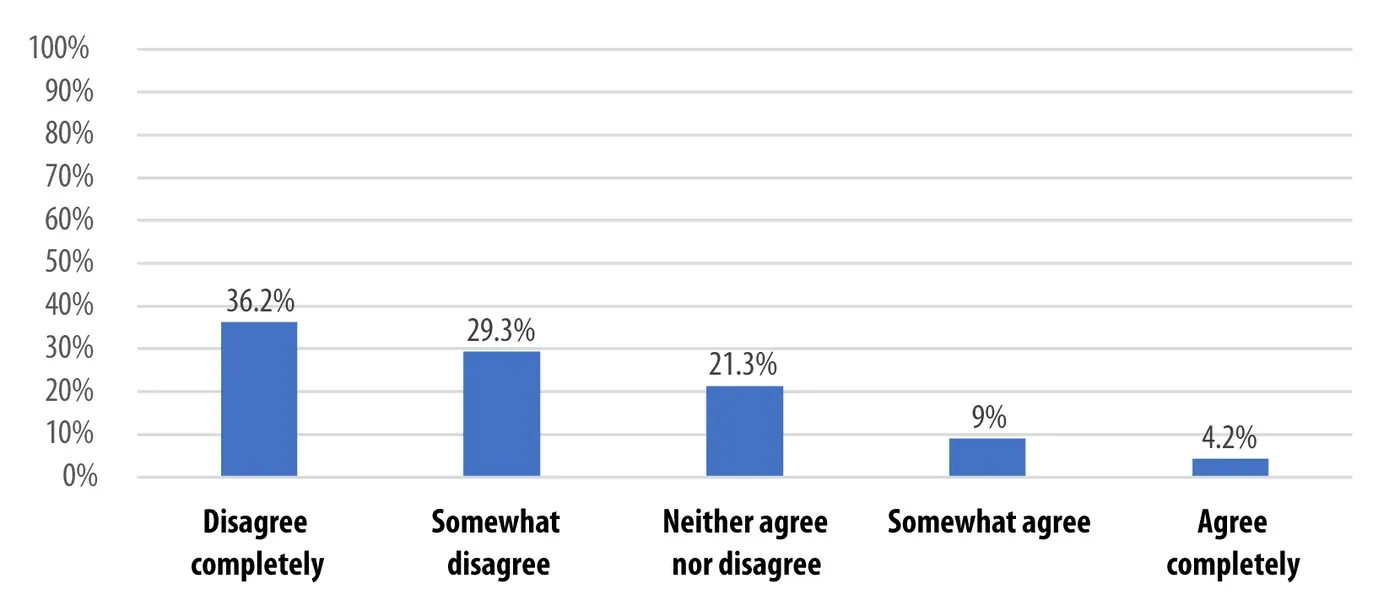

The majority of books published for children and young adults today contain inappropriate content.

Another common argument in the book challenge debate posits that a significant number of modern books published for school-aged audiences contains potentially questionable content, especially themes of sexuality. It’s hard to quantify the actual number of books falling into that category, as what’s considered “inappropriate” varies from person to person.

Regardless of the technicalities, some survey respondents stated that books with inappropriate materials (mainly sexual themes) don’t belong in a school setting or, at the very least, should be moved to a higher grade level.

“I once thought there would never be a reason to ban a book from a school library or any library for that matter. However, in recent months I have shocked myself by books dealing with sexuality targeting elementary age students. I find myself leaning to keep these types of books off the shelf until middle or high school. That said, I also believe that if a parent doesn’t care or encourages a child to read what they want, then the child should be able to have access to any book they want to read. In essence, my rights as a parent doesn’t trump another person’s right as a parent.”

“Sometimes book challenges are not outright requests for bans—sometimes they are a call for limiting access to age-inappropriate content. That is, sometimes parents want particular books to be moved from an elementary library to a high school library. Those who adamantly oppose all book challenges and book bans vilify these parents for their legitimate concerns.”

“I would like to state that asking a school library to remove sexually explicit and inappropriate books is not the same as banning them. Schools should be a safe space and there should never be pornography at school. Those books should remain at the public library and parents and kids can go on their own time to check them out … It is misleading to imply or outright accuse parents and community members of trying to ban books when we just want the books vetted before going into a school.”

“I understand that book bans limit access to books. It is up to parents or guardians to be active in their child’s education and reading experience. However, challenging the appropriateness of books is not necessarily a bad thing … Yes, some books should not be available to our younger readers, but some content may not be appropriate for all older readers either. We need to give kids a realistic view of the world, but it is okay to shield kids from some material. If we want to create a better world for the future, we must be careful not to glorify some levels of language, sex, and violence.”

At my school, parents are actively involved in their child’s education.

The level of parental engagement in their child’s education can play a significant role in discussions about book challenges in schools or libraries.

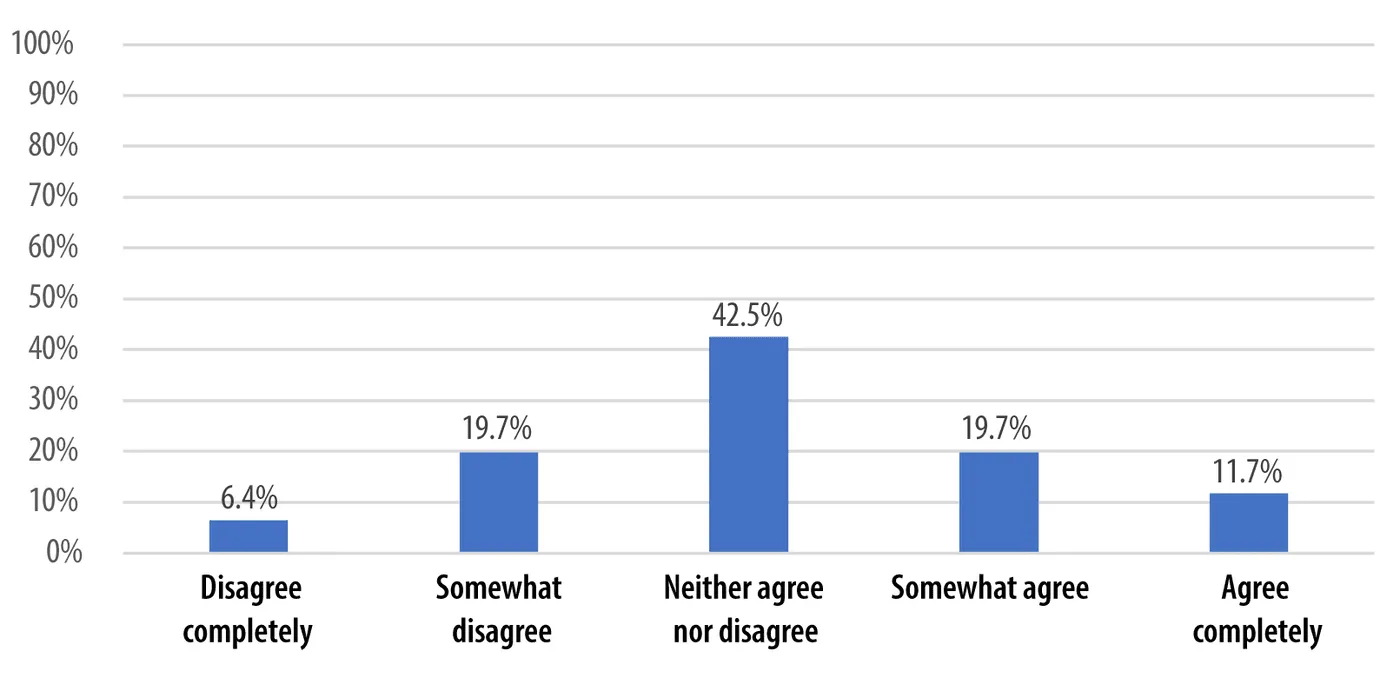

We asked survey respondents if they agreed that parents are actively involved in their child’s education at their school. Answers were mostly in the middle; the majority (42.5%) said they neither agreed or disagreed with this statement. Interestingly, “somewhat disagree” and “somewhat agree” tied for second at 19.7%. The extreme sides of the range scored the lowest, though “agree completely” had a slight edge (11.7%) over “disagree completely” (6.4%).

Some written responses explored this issue, emphasizing that parents should stay involved in what their child is learning, as that is their right. At the same time, parents should understand that their views may not align with those of other families, returning to the idea that one person’s rights don’t supersede another’s.

“I think parents should actively dialogue and read with their children of all ages. Parents are welcome to read any titles we are reading in class along with their children so that they can discuss the content in light of their beliefs and morals.”

“The argument that parents are protecting their children by banning specific books is faulty logic. I am a teacher, but I am a parent too. I want my children exposed to different ideas, cultures, beliefs. If one wants to parent and guide what their children read, then do that. But your right to do that does not supersede my rights as a parent. Be a parent and talk with your kids about what you want them to value and believe.”

“As a teacher, the rapid increase in book bans is extremely concerning. I also see an increase in parents skipping open conversations with teachers in favor of formal bans and challenges, further eroding the relationship between parents and teachers. While I support a parent’s engagement with their child’s education, I do not think it is one person’s right to remove access for all children.”

Parting Words

The subject of book challenges and bans in American schools is a complex issue that touches on fundamental principles of education, freedom of speech, and parental rights. If the responses to this simple survey are any indication, conversations are sure to continue well into the future, especially in the English language arts classroom.

As we wrap up the results of our questionnaire, we’d like to share a few more of the varied viewpoints expressed by survey respondents:

“Books are meant to be an exercise in exploration. If some ideas cannot be explored, are we truly educating?”

“The majority of time, when people object to books, they have not even read them. If we could encourage more people to read and to think critically, to foster discussion, then we could start to understand one another.”

“If books were truly ‘banned,’ then no one would be able to purchase or read them. ‘Banning’ is inflammatory rhetoric more than the actual state of affairs. Books in schools and children’s libraries do need to be age-appropriate. I do not believe public libraries are banning books for adults.”

“People don’t seem to be interested in learning about the book, but rather they just go with what others say and they assume the book is ‘bad’ just because some people have said so. If we ban one book, what is to keep other books from being banned? This is a slippery slope that we've begun sliding down and I hate to see what we will become if we continue to tell people what they can/cannot read.”

“Banning books is absurd given student access to the internet.”

“I struggle with the use of the word ‘ban.’ When parents raise concerns about a book, they are not seeking to, nor do they have the power to, ban it from being sold or read. The word inflames the conversation. I believe parents have a right to raise concerns about the content in books. I also believe that they have a responsibility to know what their children are reading and discuss it with them and not just rely on a school or library to have a sanitized collection of which they approve. We will never be able to create a collection of books that doesn’t offend someone. It’s a difficult topic.”

A difficult topic, indeed.

Thank you to all of our survey respondents. We’d love to hear from you again in the future, so please keep an eye on your email inbox for more survey opportunities.